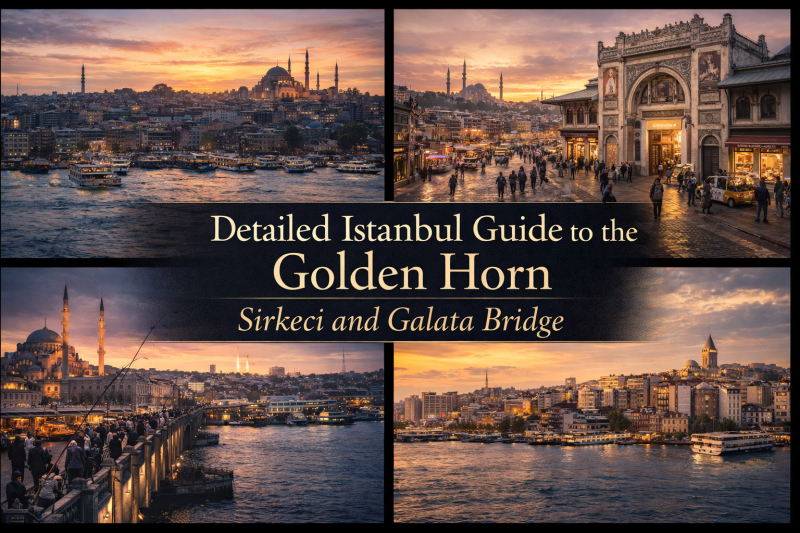

The Golden Horn, Sirkeci and the Galata Bridge:

A Poetic, Historical and Technical Journey Through Istanbul’s Living Memory

The Golden Horn does not begin with water.

It begins with breath.

A gentle, curving exhale that has shaped the heart of Istanbul for nearly three millennia.

Long before the city was called Constantinople,

and long before the world imagined an empire stretching across continents,

this narrow estuary held the rhythms of civilization

—quietly, steadily, patiently.

In antiquity it was known as the Chrysokeras, the Golden Horn.

Its crescent shape made it one of the safest natural harbors in the ancient world,

a deep, sheltered inlet ideal for anchoring fleets and building maritime power.

By the 4th century, Byzantine emperors had turned the inlet into a strategic naval base,

constructing docks, armories, repair yards, and urban quarters along its shores.

In the early Middle Ages,

the city erected one of its most important defensive structures:

a massive iron chain stretching across the mouth of the Golden Horn.

When attackers approached by sea,

the chain would be raised, blocking entry.

This ingenious mechanism—powered by capstans on the land walls—

successfully repelled multiple Arab sieges in the 7th and 8th centuries

and deterred hostile fleets for centuries.

In 1204, during the Fourth Crusade,

Venetian ships broke through after attaching battering devices to their prows.

And in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II altered the course of history

by performing one of the most extraordinary logistical feats ever recorded:

dragging 67 Ottoman ships over greased logs from the Bosphorus to the Golden Horn,

bypassing the defensive chain and rendering the Byzantine harbor ineffective.

It was an act of both engineering brilliance and military audacity.

From that moment on, the Golden Horn’s destiny shifted.

Under Ottoman rule it became a center of shipbuilding, commerce and culture.

It hosted the imperial shipyards, cannon foundries, leather workshops,

spice depots, and bustling markets.

For centuries, it served as both the industrial lung and poetic memory of the empire.

Today, walking along its waterfront,

one feels the echo of layers:

classical antiquity, the Byzantine millennium,

the Ottoman centuries, the Republican modernization,

and the living now.

All woven together in the gentle trembling of water against stone.

The Golden Horn is not a place where history happened.

It is where history continues to breathe.

Sirkeci

A Threshold Where Civilizations Crossed, Technologies Converged and Memories Took Shape

A District Built on Ancient Roads and Maritime Arteries

Centuries before the railway arrived,

Sirkeci already stood as a major crossroads.

In late antiquity it hosted parts of Constantinople’s Theodosian port complex,

one of the largest distribution centers of goods coming from Anatolia, Thrace and the Black Sea.

During the Byzantine era it functioned as a mixture of administrative hub,

commercial quarter and harbor station.

Under the Ottoman Empire,

Sirkeci evolved into a vibrant district of merchants, artisans, translators, shipbuilders,

and bureaucrats navigating the imperial capital’s maritime trade.

The area linked caravan routes from Central Anatolia

with the maritime lines connecting the Balkans, the Aegean, Egypt and Syria.

Yet the greatest transformation came in the 19th century

when the Ottoman Empire entered the age of rail.

The Construction and Symbolism of Sirkeci Railway Station

The station, opened in 1890,

was designed by German architect August Jasmund

as part of a massive transcontinental ambition:

to link Western Europe directly with Constantinople via rail.

The line was financed largely by the Deutsche Bank,

and the project symbolized the empire's effort to modernize

its infrastructure, finance and communication networks.

The station is a prime example of neo-orientalist architecture.

Its red-and-white alternating brick façade,

horseshoe-shaped arches, stained-glass windows,

and rhythmic symmetry reflect the 19th-century European fascination

with Ottoman aesthetics blended with modern engineering principles.

Technically, the building incorporates elements considered advanced for its time:

steel roof beams rather than timber,

natural light optimization through large window arches,

centralized passenger flow design,

and a telegraph-enabled operations system.

But the station’s importance was not merely functional.

It was the eastern terminus of the legendary Orient Express.

Diplomats, writers, businessmen, aristocrats, soldiers, musicians,

and adventurers arrived here from Paris, Vienna, Budapest and beyond.

The hallways carried footsteps that shaped political decisions,

letters that changed relationships,

and conversations that connected continents.

Sirkeci is more than a railway station.

It is a chamber of echoes—

a place where departures carved memories

and arrivals carried new worlds inside their luggage.

The Galata Bridge

A Structure of Steel and Symbolism Spanning Centuries of Urban Life

The Historical Evolution of a Landmark Crossing

Few bridges in the world have undergone as many reinventions as the Galata Bridge.

The first iteration appeared in 1845, commissioned by the mother of Sultan Abdülmecid I.

Constructed of wood, it was a modest structure

but a transformative one—

finally offering a stable passage between the commercial district of Galata

and the imperial center of Eminönü.

In 1863, during the extensive modernization efforts of Sultan Abdülaziz,

French engineers replaced the bridge with a sturdier design.

The modernization program included street widening, sewer installation,

harbor development and improved urban planning.

In the 1870s, Napoleon III famously proposed a monumental suspension bridge

spanning the Golden Horn,

a project far ahead of its time,

but one that ultimately remained unrealized.

The 1912 Galata Bridge, manufactured in Germany,

marked a technological leap.

It consisted of steel trusses shipped to Istanbul in sections

and assembled on-site.

This iteration survived two world wars,

the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire,

and the establishment of the Turkish Republic.

The current bridge, opened in 1994,

is a dual-level steel structure measuring roughly 490 meters.

Its bascule mechanism allows the central portion to rise for maritime traffic.

The upper deck accommodates cars and pedestrians,

while the lower deck hosts restaurants overlooking the water’s shimmering surface.

The Bridge as a Daily Poem

At dawn, fishermen line the rails,

casting their lines into the pale morning light

as though extending the city’s thoughts into the water.

At midday, the bridge hums with the layered pulse of Istanbul:

vendors pushing carts,

passengers rushing to ferries,

musicians improvising melodies,

children chasing pigeons,

and the rhythmic boom of engines beneath the steel frame.

At sunset, the Galata Bridge becomes a threshold of light.

The sky turns amber,

the minarets darken into silhouettes,

and the city seems to hold its breath

before the evening begins.

Crossing the Galata Bridge is never simply going from Karaköy to Eminönü.

It is a moment of transformation—

a reminder that in Istanbul,

every step is layered with centuries.

Along the Golden Horn

A Corridor of Civilizations, a Technical Marvel, a Living Archive

From the Galata Bridge to Eyüp,

the shoreline unfolds like a long manuscript of human history.

Here stood Byzantine granaries,

Ottoman shipyards,

Jewish, Greek and Armenian neighborhoods of Balat and Fener,

Sufi lodges, Christian monasteries,

military barracks, printing houses, synagogues, and workshops.

Along these banks,

giant dry docks were built,

timber yards carved ships for imperial fleets,

and markets overflowed with spices, fabrics, tools, manuscripts and maps.

The district of Eyüp became a major pilgrimage center

after the conquest of Constantinople,

anchored by the tomb of Abu Ayyub al-Ansari,

a companion of the Prophet Muhammad.

For centuries, Ottoman sultans held their sword-girding ceremonies here—

the imperial equivalent of a coronation.

In the 16th century,

the great architect Sinan designed aqueducts, mosques and urban complexes

that still shape the identity of the Golden Horn’s northern banks.

In the 19th century,

industrialization brought factories, foundries, rail lines and new piers.

In the 20th century,

republican modernization reshaped the waterfront with roads, parks and museums.

Today, the Golden Horn is a place where:

ancient geography,

Byzantine engineering,

Ottoman naval architecture,

and modern urban design

flow together in the same quiet curve of water.

Walking here is not merely a walk.

It is an act of reading time.

A Poetic Invitation to Discover Istanbul More Deeply

After witnessing the quiet glow of the Golden Horn,

after listening to the echoes inside Sirkeci Station,

after crossing the Galata Bridge with the city breathing beneath your feet,

you may feel that your journey has only begun.

Istanbul is not a destination.

It is a story that continues.

To explore daily tours and activities that reveal more of the city’s history, culture and hidden chapters,

you can visit the page below:

Istanbul Daily Tours and Activities

https://vigotours.com/things-to-do/daily-tours-activities/istanbul-turkey/all-categories